A First Principles Guide to One-on-Ones (Part1)

The one-on-one is so ubiquitous in its application and yet so broad, or vague, in its structure and purpose that I have decided to start from first principles to make a guide for it. Inevitably, this has made this piece a lot longer than I had initially planned, and so, for easier digestibility, I have split it into 3 sections: the WHY of one-on-ones (including why they are great despite Jenson Huang and Elon Musk), the WHAT to do in a one-on-one, the topics and contents that make it most valuable, and lastly HOW to run a one-on-one, the execution. Parts 2 & 3 will come out shortly, so you can confidently start reading Part 1 now.

WHY do one-on-ones?

One-on-ones are the most basic type of meeting imaginable: two people talking with each other periodically. They are also the bread-and-butter artefact of leadership: a private, direct dialogue between a leader and a direct report.

There are opinions out in the wild that one-on-ones can also be had with skip-level reports. I strongly disagree. It´s fine to check in with skip-level reports once in a while. In fact, I recommend checking in with people from various levels of your company now and then, but if you should ever feel the need to have frequent, structured meetings with skip-level reports, you should probably get rid of the middleman.

Alas, from the perspective of a founder or CEO, they are quite the investment. You typically have more than one direct report, and your time is the most limited resource the company has (everything else can be sourced). By nature, the one-on-one does not scale. So there better be a good reason for you to take time for your direct reports individually and not as a group.

And there is a very good reason indeed: as a leader, the only way for you to scale is through your direct reports. Scaling means creating more output from the same input. The input is your time. The output is decisions (to be clear: a decision is not an act but a process that starts by gathering the intel to decide in an informed way and only ends when either its goal is achieved or the decision gets consciously reversed). As your organisation grows and takes on leadership levels, the breadth and depth of decisions becomes unmanageable for one person. You need people, first and foremost your direct reports, to make them on your behalf. This only works,

- If your direct reports decide and act based on their own judgment without involving you (or else you are only buffering decisions that will still be made by you, thus not saving you time), and

- If they do so in alignment with you (or else you will spend any time saved deciding on fixing…and probably more than that).

This crucial ability to decide autonomously but aligned is based on two things: the quality of your direct reports (their capability and knowledge to make decisions based on existing or deductible patterns of thought) and the quality of your relationships with them (the swiftness, clarity, openness and robustness with which you can exchange views on matters and align when new patterns of thought are needed or the application of existing patterns is unclear).

And this is exactly why you have one-on-ones. You have one-on-ones to develop the quality of your direct reports and to develop the relationship you have with them. And because both are personal, sometimes sensitive matters, they require openness and trust from both sides and a willingness to sometimes go where it hurts. And the one-on-one provides the best setting for this: confidential and with no competition for airtime, no peer pressure, lower risk of embarrassment and more bandwidth to read emotional clues.

In short, one-on-ones are the fundamental tool to enable you to scale yourself, and it’s hard to imagine a leader’s toolbox without them.

And yet, there are at least two outstandingly successful leaders who don’t do one-on-ones (at least not in a regular sense): NVIDIA’s founder-CEO Jensen Huang and Elon Musk.

This begs the question: are they right? I can hardly argue that they are wrong, because they’ve managed to build very successful organisations - in Musk`s case, more than once. But I will argue that their take on one-on-ones is inefficient for most leaders.

I will base my argument on a quote that Jensen Huang gave in an interview as his reason for not doing one-on-ones (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8egG-Nts1ac). He said: “Almost everything that I say, I say to everybody all the time. I don't really believe there's any information … that only one or two people should hear about.”

I think this statement is correct only in a pretty narrow set of circumstances.

During my 11+ years as a CEO, I’ve had leadership teams of varying seniority. Junior in my early years, senior in my later years. But at no point in time did my one-on-ones contain a majority of information that was relevant not only to the respective direct report but to most or all of my direct reports. In fact, I would estimate that only about 15% of what I spoke about during one-on-ones was “generally relevant information”, such as first principles thinking, thoughts on strategy or company priorities, insights on the market or thoughts on macroeconomics, leadership principles, values, etc. The other 85% consisted of “individually relevant information”, which was not pertinent to my other direct reports, such as specific feedback or observations, my perspective on issues my direct report sought advice on, aligning on matters specific to my direct report’s role or responsibilities, motivational or private matters, and so on.

I believe this or a similar split is rather common, and in my experience, the share of generally relevant content is usually even lower in startups.

If your split is similar to mine, then getting rid of one-on-ones is inefficient. You would be wasting a lot of time of your direct reports (listening to individually relevant information that is not relevant to them) while saving only very little time yourself (because you can only save time on the generally relevant information).

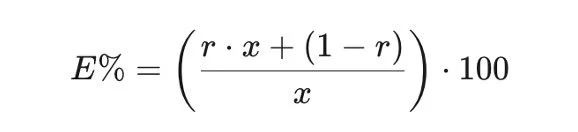

If you want to do the math yourself, here’s the formula:

“E%” is the efficiency ratio of moving one-on-one content to group meetings. It has two input parameters: the ratio of generally relevant content “r“ (between 0 = none of the one-on-one content is generally relevant, and 1 = all of it is generally relevant) and the number of direct reports “x”. With the E%, we can then calculate how much time is saved or wasted by getting rid of one-on-ones.

Having had an “r” of 15% or 0,15 and an “x” of 8, my resulting “E%”, had I made all my one-on-ones into group sessions, would be less than 26%. This means I would have wasted more than 6 hours of meeting time of my direct reports (74% of 8 hours) while saving only about 1 hour of my time (15% of 8 hours).

Jensen Huang has 60 direct reports. This lowers his “E%” even further (at the same “r” of 0,15) to a meagre 16,4%. How can this approach work for him?

There could be two reasons:

- A homogenous & very senior composition resulting in a much higher “r” (> 0,5). In the interview, Huang said: ”I love that there’s no privileged access to information, that we’re all able to contribute to solving a problem and that when you have 60 people in the room, everybody heard the reasoning of the problem, everybody heard the reasoning of the solution”. This gives me the impression that the areas of expertise and responsibility of his group of 60 are less segmented or mutually exclusive than was the case in my leadership team (or any other leadership team I know of). And a bigger responsibility or problem-solving space overlap effectively increases the share of generally relevant content. Also, it is safe to assume that the members of his leadership group are all of exceptionally high ability and seniority, and do not need much individual input to do their work well, effectively lowering the share of individual relevant content.

- A (compensating) positive efficiency effect due to fewer layers of management. In the interview, Jensen estimates that, by having 60 direct reports, he has removed “about 7” layers of management. Even if that’s probably a bit exaggerated (with a 7-to-1 reporting ratio, it’s more like one or two layers), it does have the potential to make communication more direct and efficient and can offset a negative E%.

So, even if it’s a bit of a stretch for me, I can imagine that his system works for him. But only because he works with a group of people that does not require much individual input and/or works on a similar set of problems a lot of the time. And only because he can manage 60 direct reports while still being able to get his head above the operational water-line and have the clarity to develop powerful strategic thoughts.

If this is you… try it. I know it’s not me.

Elon Musk, on the other hand, seems to be principally ok with one-on-ones. He just does not like meetings. Particularly not the scheduled type, and particularly not ones that exceed a couple of minutes. As a result, his one-on-ones are very short, spontaneous and focused purely on operational issues. Like Huang, Musk is capable of steering his companies with minimal management layers and leadership development, but – in complete contrast to Huang – not, because he has organised his teams in a way that allows him to address most of his reports as a group, but because he can talk with everybody individually about totally different things, down to operational details, at any time, all of the time. Musk seems to be oddly capable of constantly switching context and focus while still functioning at a very high level. And it’s this context switching that most other human beings simply cannot do well. Focus requires energy, and frequently refocusing drains us, making us inefficient thinkers. And so this ad-hoc micro-management style is not efficient for most. Again, I know it’s not efficient for me.

Ok, time to get back to where we left things before I took us down the rabbit hole: the purpose of one-on-ones is to develop your direct reports as well as your relationship with them. And being clear on this purpose is critically important, because

- Without this purpose in mind, you cannot possibly determine the duration, frequency, participation or meeting rules of the one-on-one.

- Without this purpose in mind, you will not feel that your one-on-ones constitute a productive part of your day, and you will not fully engage in them. In return, you will not get much out of them, and that will make you look forward to them even less. Ultimately, without a clear purpose, your one-on-ones are going to feel like a waste of time for both you and your direct report, something that you are somehow expected to do but don’t enjoy.

But how exactly does this purpose translate into the design of the meeting? Continue reading in Part II to find out (to be added next week).nd out